In April 2013, at the same time as I was struggling to cope on a pitifully inadequate dose of Levothyroxine, one of our esteemed endocrinologists was giving a paper to the American Thyroid Association at a research summit called “Treatment of Hypothyroidism: Exploring the Possibilities”. “Exploring the possibilities” suggests cutting edge research that might improve the lot of those who endure the life-limiting condition that CAN be hypothyroidism. Here, you might think, was an exciting opportunity to think outside of the box. Instead he slammed the lid firmly shut with a strange and, at times, contradictory paper called “Challenges of Therapy: Dissatisfaction with Thyroid Hormone and Somatization Disorder”. As the paper progressed what the esteemed endocrinologist had to say took a very dark turn.

This is my story and I am going to show you how I stumbled into the scandal that makes some health professionals treat those with thyroid disorders as if it is “all in the mind”.

For about a decade before I was diagnosed as hypothyroid I struggled with the symptoms. During what I now refer to as “my lost decade” my TSH was such that I didn’t qualify for treatment even though my FT4 results, although in range, were very low. I didn’t know this at the time, but recently I have had access to my medical records dating back to 2005. I had already endured two or three years of deteriorating health by that point. From then until 2011 my thyroid function test results slowly, but consistently, deteriorated. This was still two years prior to diagnosis. I felt very poorly but had no idea why. At the time I wasn’t even aware that my GP was testing my thyroid function. I was aware that she was running a panel of tests, but I was simply told that, with the exception of recurring bouts of anaemia, the results were “normal”. With the benefit of hindsight I should have questioned my GP more closely. She was, however, of the school that believes that “unless you are a trained health professional you won’t understand” (her words). A thyroid problem certainly wasn’t on my radar despite the fact I was experiencing a myriad of other symptoms that included aching joints, hair loss, headaches, gynae problems and raised cholesterol to name but a few. I appreciate that hypothyroidism can be difficult to diagnose, not least because the symptoms are somewhat nebulous, but one would have thought that the symptoms and borderline results together should have prompted further investigation. In his lecture on the “challenges of therapy” the esteemed endocrinologist dismisses thyroid hormone replacement in “biochemically euthyroid individuals”. Presumably I fell into this category. When I think about it now, it’s laughable. Someone wasn’t joining the dots. No, worse! My GP treated me as if I had a somatoform disorder. September 2009, I distinctly remember her saying “I’m not going to tell you that there is something wrong with you” to which I replied, “I just want to feel better”.

Feeling unwell like that for such a long period of time grinds you down. During my lost decade I began to suffer badly with anxiety. Quite simply, I felt overwhelmed as I struggled to juggle ill health and daily life. By June 2012 I was on my knees. “I’m sorry to bother you again, but I feel absolutely grotty” had become the prelude to every appointment with my GP. I reeled off the well-worn list of symptoms. On this occasion I concluded with “I think it’s hormonal” ( ….so close!). “Please could I have some blood tests?” Her reply was peremptory, “we don’t do blood tests on women your age” and I was fobbed off with some Migraleve. If you are deemed to have a somatoform disorder your health practitioner will have stopped looking for answers to your physical symptoms. I was treated like a time-waster.

It is perhaps appropriate at this point to consider what constitutes a somatoform disorder. I am going to call it that because it is the name we are familiar with whilst acknowledging that “Somatic Symptom Disorder” (SSD) is the current preferred nomenclature, previously in the USA “somatization disorder”, hence the title of the unfortunate paper. Anyway, in the not too distant past you were deemed to have a somatoform disorder if you experienced physical symptoms that could not be attributed to any conventionally defined medical condition. Those symptoms would have to be very distressing or result in significant disruption of functioning, as well as excessive and disproportionate thoughts, feelings and/or behaviours. If I say that hypochondriasis fell within the spectrum of somatoform disorders you can begin to appreciate which ball park we’re in here. It is worth noting, however, that studies on somatic symptoms and disorders have been hampered by lack of a valid and reliable diagnostic classification. Indeed, if you GOOGLE it, it can be difficult to pin down an exact or simple definition. Perhaps reflecting this state of affairs is the fact that in the most recent edition of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) a change in emphasis means that the somatic symptoms can now be associated with another medical condition that you are known to have. So where does this leave those patients who, like myself, are eventually found to have a condition whose diagnosis and management can be somewhat problematic?

I am fully aware that the journey I was about to undertake in order to regain some quality of life could be classed as a “disproportionate” pre-occupation with my health. Presumably while esteemed endocrinologists are allowed to “explore the possibilities” patients are not! I’ll leave the decision to you as to whether I have a somatoform disorder when you have read about what transpired over the course of the next two years.

I have always worked on the principle that prevention is better than cure and if I could possibly get to the root of the problem that had prompted my GP to prescribe the Migraleve, that would, as far as I was concerned, be the preferred option. I mean, who wouldn’t do this? I had already ruled out the most obvious migraine triggers. I felt strongly that the problem was hormonal in origin and as my GP had refused to look into this I ventured into the world of private testing. The company I approached put me in touch with a practitioner who lived locally, a BANT-registered nutritionist, who would lead me through a process. As I awaited the results events intervened. Stumbling around in a dull-headed fug I fell, not for the first time, and broke another bone. After a catalogue of broken bones my GP could hardly refuse me the bone density scan that I asked for. A month later when the results were in she didn’t even take her eyes off her computer screen as she told me that I had osteoporosis and that I would be referred to a rheumatologist. Not realising what a contentious issue adrenal fatigue is I had quite innocently taken along the private test results. My DHEA was low and buried amongst the accompanying notes was the following: “decreased DHEA levels may be seen in thyroid disorders”. She dismissed the tests without even looking “You don’t want to waste your money on those!”.

October 2012: I prepare carefully for the appointment with the rheumatologist. Here at last I might encounter a health professional who will help. I still have the sheet of paper where I have noted down points that seem relevant: “weakness, headaches, anxiety, poor immunity, hair loss and sleep problems”. In his lecture the esteemed endocrinologist’s slides refer to statistical measures of “QoL”, Quality of Life. If we’re talking about “quality of life”, let me tell you about the reality of that list. My sheet of paper also contains the following details:

“Headaches that persist for 3-4 days at a time. Pain relief is largely ineffective”. (By this point I had headache more days than not.)

“Low level flu-like symptoms that last for months: aching, washed out, lacking energy.”

And tellingly…

“Would describe myself as running on empty. It’s like something has ‘knocked my system out of kilter.’ ”

Quality of Life trips of the tongue easily when you are dealing with statistics. My list gave voice to what had become an unpleasant struggle, a joyless existence.

I take time off work to attend the appointment and I have asked a friend to accompany me. We wait for about an hour before I am called through to be weighed and have my blood pressure taken. Time ticks on. I’m not going to get back to work this afternoon, but it doesn’t matter. Perhaps this appointment will be the first step on my road to recovery. My name is called. We go through and the consultant waits for us sit down before he says “I haven’t had the letter of referral from your GP. I can’t see you without it”. His face is dead pan. “But I’ve been waiting for this appointment. Can’t you contact the surgery? I’m sure they will fax it across.” His face doesn’t change. “You’ve already weighed me and taken my blood pressure.” He glances cursorily at his computer screen showing my results. “There’s nothing wrong with you. Make another appointment at reception on your way out”. I have since discovered that the notes accompanying the DEXA scan identified bone density “markedly reduced with own age group”.

I don’t know what that guy was thinking, but I would imagine that if you are considered to have a somatoform disorder you regularly encounter such treatment. Numb with disappointment and anger I book another appointment on my way out. The following day, when anger gets the upper hand, I cancel it. I refuse to see the consultant I had seen the previous day and in doing so point out what a waste of valuable NHS resources the previous afternoon had been. I am told that there is an appointment with another consultant but that I will have to wait longer. “I’ll wait!”

A month later and the new rheumatologist is listening intently to my concerns. I have the letter she sent back to my GP in which she outlines a treatment plan for the osteoporosis. She also, however, wrote “T4 is reduced suggestive of borderline hypothyroidism…..the TFTs should be repeated in due course as they may be suggestive of evolving hypothyroidism.” I start treatment for the osteoporosis and my GP asks me to have another blood test. I know now that it was a thyroid function test but this time also measuring peroxidase antibodies. The results confirm that my FT4 has dropped below range and the peroxidase antibodies are elevated. It is November 2012 and the first time my GP has started to dig a bit deeper. No one calls, however, to say that I need to book an appointment and start treatment for a thyroid problem. It is mid-January before I visit the surgery again. My GP tells me that I am hypothyroid. “The good news is you get free prescriptions. Pick up a form from the receptionist on your way out” she says briskly. Beyond that, I am on my own. Keen to commence treatment I go straight from the surgery to the chemist to pick up my prescription. It’s busy. There are several people in front of me and several behind me in a long queue. I get to the counter. I hand over the paperwork : “Apparently I get free prescriptions” “Yes, it’s because you have a lifelong condition”. My first lesson on hypothyroidism!

A couple of days later I have an appointment with a haematologist. I have once again taken along the trusted friend whose support has never wavered when others have drifted off and lost patience as I have dealt with the fall-out of my poor health. She is fascinated by the story unfolding. The DEXA scan also came back with the following note: “Further investigation to exclude other underlying causes for the reduction should be considered with specialist referral”. My GP has been galvanised into action.

The haematologist is thorough. He frequently refers to a computer screen showing my test results, then brings up other screens with different graphs showing trends as he tries to figure out what’s going on. It feels high tech, but he is also asking lots of questions and listening carefully to the answers. I discover that my Ferritin is 4. So, I clearly need iron. (I think of the gynae issues I have raised with my GP and the blood tests I was refused.) The haematologist brings up another screen showing my full blood count results going back 13 years; 25 tests in all. In the first column (white blood cell count) all but three of the results are highlighted in red as “abnormal” or “critical”. I had already worked out for myself that my immune system wasn’t functioning properly and was taking something from the local health food shop to try and deal with it, but this is a revelation. My friend quick as you like says “Please can we have a print-out of that?” “No problem, just ask the nurse on your way out.” He wants to investigate this low white blood cell count further. He orders more tests and feels my arm pits and my groin. My system is so depleted he wants to rule out Hodgkins Lymphoma. Thank God it isn’t. It is in fact good news that these problems haven’t had a sudden onset and that they stretch back years. Physically, I am at the bottom of it. I feel dreadful, but I am no longer dismissed and treated as though I have a somatoform disorder.

January 2013: I commence treatment for hypothyroidism with 25mcg Levothyroxine and I am instructed to come for a follow-up blood test in three months. This I duly do - to the day! At the follow up only my TSH is tested and it comes back 1.87miu/L (0.35-5). I don’t feel any better but my GP isn’t prepared to enter into any dialogue about that. My concerns are dismissed. In his lecture the esteemed endocrinologist suggests that “If a patient is dissatisfied with thyroid hormone replacement therapy titrate TSH levels below 2 mU/l and advise about missed doses.” I have two problems with this: 1) I don’t care what my TSH was, I still felt dreadful. 2) I hadn’t missed any doses. In fact my experience is that we all take our thyroid meds with military precision.

The reason I wasn’t feeling any better would, according to the reasoning of our esteemed endocrinologist, be due to “a somatization disorder”. In June, feeling worse still, I return for another appointment. On this occasion I am armed with knowledge and I ask when I might conceivably start to feel better and "please could you tell me what my result are". I mention T3 testing but it is brushed aside and I am told that unless I am a trained professional I won’t understand. I walk home from the surgery weeping.

One of the reasons that the esteemed endocrinologist gives for the “silent epidemic” that results from somatization disorders is a “decline in medical prestige” and “healthism”. He takes the trouble to define healthism as including “high health awareness and expectations” and “information seeking”. It’s June 2013 and I don’t know where to turn for help. I recognize that I have lost a decade of my life to this condition and there is a growing realisation that 25mcg Levothyroxine isn’t going to work. At this point I would simply have said to the esteemed endocrinologist, “If you give me answers, I won’t go looking!”. It is six months after commencing treatment for hypothyroidism that I stumble upon this forum. A month later I become a member of Thyroid UK and change my GP.

Let’s stop and think about the wider implications of my story so far.

In his lecture the esteemed endocrinologist refers to the group of patients “who are demanding thyroid treatment when they are not hypothyroid” as well as “a number at least, and I would say a fair number of those, that still feel unwell despite hormone treatment when they’re hypothyroid.” He concludes that their symptoms must simply be somatic. Warming to his theme he asserts that consultations wasted on such patients are “medicine’s dirty secret” and are “a huge drain on healthcare.”

I would like to suggest quite the opposite. Putting right the damage that an untreated thyroid problem wreaked on my system cost the NHS dearly. Did I mention that in addition to the appointment with the rheumatologist I have also had multiple appointments with the haematologist, a gynaecologist and psychological support. And what about all of those unfortunate appointments with my GP and the endless prescriptions as I struggled to cope with my poor health.

My story is far from unique. This is the real “dirty secret” of medicine. IT IS THE POOR DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF THYROID DISORDERS THAT ARE "A HUGE DRAIN ON HEALTHCARE".

While we’re talking about appointments, the esteemed endocrinologist also has some tips on “the consultation”. While acknowledging that “although we have problems with our patients” he nevertheless advises that “we have to stick by our guns”. So what does he mean by this? He gives three examples of those bothersome patients:

•a patient who’s got a belief that they need more thyroid hormone.

•they need T3 or

•they need to be on T3 and T4 even when their TSH is normal

So what does he suggest? “INTERACTIONAL RESISTANCE”. If you’re wondering exactly what that entails, fear not, he elaborates: “Interactional resistance….through disagreements, challenges, rejections or passively (through lack of engagement, silences or the use of minimal responses).”

I was nervous about the “interactional resistance” I might encounter in the first appointment with my new GP. What I found was a respectful dialogue. A somatoform disorder clearly wasn’t on her radar as she said “Let’s increase your dose to 50 mcg and let’s test your T3”. God bless her! The T3 results were revealing and despite several further increases in Levothyroxine my T3 stubbornly languished below range. (Goodness knows what it had been all of those years without treatment.) I was still experiencing symptoms. What next? More “information seeking”. I was still indulging in what our esteemed endocrinologist refers to as “healthism”.

I think it is an appropriate moment to stop and consider what the esteemed endocrinologist says about “healthism”. He poses a question: “So what is healthism really about fundamentally?” His answer: “It’s about consumerism!”

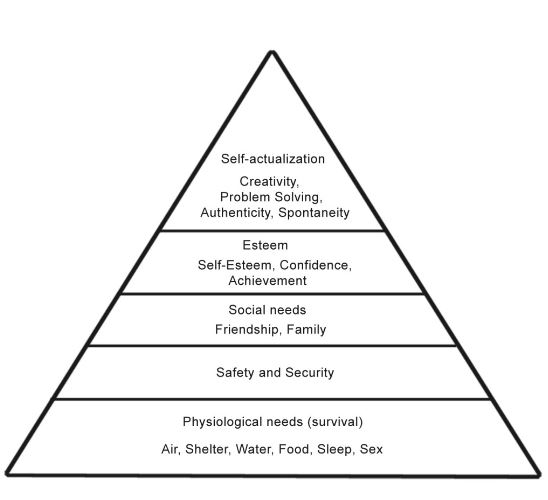

Referring to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs (see diagram) he asserts that in Western society “we have overcome all of our base needs. We’re safe, we’re loved we feel we belong we’ve got self-esteem and therefore we’re reaching the top of Maslow’s pyramid”.

He suggests that “through the conflation of health and consumerism, or by health being commercialised, men and women are subjected to the mechanisms of advanced capitalism” which is “a burgeoning problem for society.” In simple terms, we want too much! Elsewhere he refers to “lifestyle endocrinology”. How dare he! On the contrary, I would suggest that if I am in poor health my base needs are NOT met. And what about “social needs” and “self- esteem”? I think the following snippets from my diary say it all:

“I find that I have to focus very hard to keep my head above water at work these days. I frequently make mistakes. My self-confidence has taken a massive hit”.

“In the office I feel like a fly on the wall. On those days when I am really struggling, when I am mute and dull-headed and when I have to go straight to bed when I get home, I observe my colleagues laughing and talking, full of energy, taking their stamina for granted, confident to take on new challenges. And although I don’t like myself for it, I feel envious.”

As my health deteriorated, so did my self-esteem, my relationships and while we’re at it…my livelihood. At the beginning of my lost decade I had a successful career, working full time and coordinating a team of about 40 staff. I stepped down at the end of 2004 thinking that my health might improve. Little did I know what lay ahead. By the time I was diagnosed nearly a decade later I was struggling along on just two days a week as the least senior member of the department. Is good health too much to ask for?

At the beginning of his presentation the esteemed endocrinologist on introducing classical hypothyroidism declares that: “It’s very, very easy to deal with you just give thyroxine and the patient gets better”. I have my fellow HU compatriots to thank for spotting that the “before” and “after” pictures that he has chosen to support his flippant assertion are those of a woman treated in the early 1890s. Our esteemed endocrinologist was surely aware as he rejoiced in the work of George Murray that the woman was treated with natural thyroid extract, a treatment that he is to denounce just moments later. (One wonders whether he was being deeply ironic.) Likewise, when he starts to consider at length the pharmacological, physiological and genetic factors that might confound trials evaluating combination therapy, it becomes blindingly obvious that hypothyroidism is not at all “easy to deal with”. He notes that “variability in deiodinase enzyme and thyroid hormone transporter distribution, including genetic polymorphism” means that “specific tissues might be underexposed to sufficient T3” especially considering that “FT3 and TSH levels poorly reflect how much thyroid hormone (as T3) the rest of the body tissues are exposed to” (his words!). Another problem that he considers is that treatment-wise it is difficult to mimic the circadian rhythm of T3. If we’re talking about military precision in order to optimise our doses one need look no further than Paul Robinson. If anyone’s been “information seeking” he has! Oh, and while we’re at it, I bet Paul doesn’t need advising about missed doses!

When 100mcg wasn’t enough I could have stopped “information seeking” and my GP could have treated me like I had a somatoform disorder. But I didn’t and she didn’t. Healthism might be about consumerism, but the cost of the test to determine whether I have the polymorphism in the DIO2 gene is the best £120 I ever spent! The results confirmed that I have inherited the problematic gene from both parents. The esteemed endocrinologist himself cites the prevalence of the polymorphism as affecting 16% of the population. That’s a lot of people. I would like to remind him that he himself recognises that “variability in deiodinase enzyme and thyroid hormone transporter distribution, including genetic polymorphism” means that “specific tissues might be underexposed to sufficient T3” which could explain why, to use his own words again, there is still “a number at least, and I would say a fair number….that still feel unwell despite hormone treatment when they’re hypothyroid.” (Funny that…..I wonder why….) So why is the DIO2 test not offered as a matter of course when patients report that Levothyroxine isn’t working for them? I wonder, as they were “exploring the possibilities” at the research summit, whether anyone thought to suggest that. I also find myself wondering if a paper such as this was all that our esteemed endocrinologist had to bring to the table at a research summit “exploring the possibilities”. I acknowledge that I am lay-person and that research-wise there are layers of complexity about which I am completely ignorant, but why, when there is such a growing and increasingly vocal body of patients dissatisfied with the ONE (yes, ONE) medication offered under the NICE guidelines for hypothyroidism, have we reached a dreadful impasse where all that those unfortunate patients can expect is “interactional resistance”. Just as we need the brilliant minds of those carrying out research, they too need to respect that the thyroid patients themselves are their most valuable resource. We patients are the “experts” who live with this condition day in, day out.

When I took the DIO2 results to my GP I wasn’t greeted with “interactional resistance”. I said, “Perhaps this won’t be the answer, but I’d like to try a combination of T4 and T3”. I think she sees an individual who is realistic and pragmatic, who simply wants to get on with their life. I, in turn, respect her opinion. We had a discussion, she agreed to give it a go and I am deeply grateful that I was able to take another huge step on the road to recovery.

Now, I’m no expert on somatoform disorder, but for me the esteemed endocrinologist’s argument simply doesn’t stack up. Before my lost decade I was living a full and active life with a successful career and a GP who saw me infrequently. Indeed, I rarely thought about health problems. Then I develop a range of unpleasant symptoms that seemingly cannot be explained: a somatoform disorder? I receive a diagnosis that explains the symptoms: maybe not a somatoform disorder after all. The treatment that I receive does not alleviate the symptoms, so the somatoform disorder returns. Then I receive treatment that works and the somatoform disorder disappears again. Just like that! “Now you see it…..now you don’t!” The attitude of some of the health professionals that treated me (or rather, failed to treat me) had me too believing that it was all in my mind. Today, in better health and with a clear head, I can see the situation for what it was and appreciate how a nasty condition crept up on me and robbed me of the wherewithal to fight my corner. Incidentally, I rarely see my GP these days.

Is this how a somatoform disorder works? Does it really come and go so readily? While I am happy to acknowledge that somatoform disorders exist I am angered and saddened that there are thousands of thyroid patients who are still struggling to shrug off this unhelpful label.

One of the “take home messages” with which the esteemed endocrinologist concludes his unfortunate paper is “When a patient feels unwell with a normal TSH, there is no place for the addition of T3 to T4: seek another cause”. If, as his paper suggests, that other cause is “somatization disorder” the next step is very easy. As far as mental health is concerned, the words “stigma” and “discrimination” come to mind.

To conclude, this is my “take home message” to the esteemed endocrinologist:

Any attempt to convince someone that they don’t know their own mind, and coercing others to perpetrate similar is, I believe, a form of abuse. If this is the message that you pedal, what hope have we when those of us with thyroid disorders turn to our primary-care practitioners for help. At the very least, a stance like this is designed to disempower the patient. And if we are talking disempowerment and abuse, then we are talking about human rights. So, what I say to you esteemed endocrinologist is “I WILL NOT BE SILENCED!”