For anyone who is interested in wading through the technicalities here is the definitive medical text on how we got to this place -

Journal of Clinical Pathology

The Surgeon's Perspective on Oesophageal Disease, and What It Means to Pathologists

Christina L Greene, P Michael McFadden

Disclosures

• Abstract and Introduction

• GERD

• Barrett's Oesophagus

• Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma

• Summary

• References

J Clin Pathol. 2014;67(10):913-918.

Abstract and Introduction

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has become the most important oesophageal issue of the 21st century. It is defined by the Montreal

International Consensus as a 'condition which develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and or complications.'[1] To

surgeons, its importance lies not only in its prevalence but, more importantly, in its potential to lead to adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus. GERD affects

between 18% and 28% of the US population, and approximately 8%–15% of these patients will go on to develop the premalignant condition of Barrett's

oesophagus.[2–5] The two most prevalent types of oesophageal carcinoma are squamous cell and adenocarcinoma. Squamous cell carcinoma used to be the

most prevalent oesophageal cancer in the Western world, but it has been surpassed by oesophageal adenocarcinoma in the last 40 years.[6] Oesophageal

adenocarcinoma primarily affects white men with GERD, while squamous cell carcinoma is more commonly associated with tobacco and alcohol use.[6]

Oesophageal adenocarcinoma is an extremely lethal form of cancer with a five-year survival rate of 15%–20% despite best available therapy. The five-year

mortality rate in early stage disease has been reported to be as high as 63%.[3,7–10] GERD is a prevalent disease affecting nearly one-quarter of Americans

and Barrett's oesophagus is a known complication of GERD.[2] For clarity, Barrett's oesophagus is defined as specialised intestinal metaplasia of the

metaplastic columnar epithelium.[11] Of those with Barrett's oesophagus, approximately 0.12%–0.38% per year will progress to oesophageal

adenocarcinoma.[11,12] We know that chronic GERD leads to Barrett's oesophagus, which is a precursor to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Since we have

effective treatment for Barrett's oesophagus, why then does the incidence of oesophageal cancer continue to rise in the USA?[10]

Since the 1970s, there has been a nearly 400% increase in the incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma.[13] Less than 5% of patients who develop

oesophageal adenocarcinoma have a previous diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus, and 38%–50% of patients with oesophageal adenocarcinoma present

with metastases.[9,13,14] Physicians and surgeons are not adequately identifying patients at risk for Barrett's. We are failing to refer these patients for early

evaluation and intervention of this potentially preventable disease. Instead, patients are presenting late after they have already developed invasive

adenocarcinoma. At this late stage, surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy are often only palliative.

Like obesity, GERD has become a public health problem which requires attention from all specialties.[15–18] In general, the goal of oesophageal surgeons is

to first control GERD by a combination of medical and surgical therapy in order to prevent the development of reflux oesophagitis and subsequently

Barrett's oesophagus. If Barrett's oesophagus is already established at the time of patient presentation, the focus is then on monitoring the oesophagus for

the early signs of dysplasia. If dysplasia is present, eradication of Barrett's oesophagus using radio-frequency ablation (RFA) or endoscopic mucosal

resection is appropriate. If a patient is non-responsive to less invasive therapy, or progresses to invasive oesophageal adenocarcinoma, oesophagectomy

with oesophageal replacement is frequently indicated in the absence of distant metastases. If metastasis has occurred, then chemoradiotherapy or hospice

care may be appropriate. The focus of this review is to provide an overview of the various surgical treatments for GERD, Barrett's oesophagus and

oesophageal adenocarcinoma in order to help demystify the surgical treatment of this disease for pathologists. Major advances in diagnosis and prevention

of this disease will likely come from histopathologists who can characterise the details of disease progression. A common language should then be

established between surgeons and pathologists to integrate clinical and pathological information to better manage patients in the future.[19]

The diagnosis of GERD is first suspected based on patient symptoms, most commonly heartburn and regurgitation. However, it must be established by a

meticulous work-up, which involves upper endoscopy with biopsy, a barium swallow study, pH monitoring and oesophageal manometry. During upper

endoscopy, if a columnar lined oesophagus is observed, the Prague classification should be used to describe the length of the Barrett's segment in a

standardised manner.[20] Biopsy during initial evaluation for GERD is important to confirm Barrett's oesophagus as this will likely need to be ablated prior to

surgical fundoplication. Four quadrant biopsies every 2 cm are performed along the Barrett's segment according to the Seattle protocol.[21,22] If Barrett's

oesophagus is not present, the symptoms may be managed with medical therapy alone (proton pump inhibitors, H2 blockers, antacids and antireflux

precautions, etc.). If symptom control is ineffective, oesophagitis is present, or the patient prefers surgical repair, then several antireflux operations are

available. The 360° Nissen fundoplication is the gold standard and most popular antireflux surgical procedure in patients with adequate oesophageal

motility (figure 1).[23–25] The 270° Toupet fundoplication is a less common but effective alternative to the Nissen fundoplication (figure 2).[26] This approach

is more often reserved for patients with poor oesophageal motility to avoid postoperative dysphagia and obstruction. A less invasive approach is the use of

the LINX® antireflux system which can be performed in patients with uncomplicated GERD (figure 3).[27] The main surgical principles of a Nissen

fundoplication are listed in the Box 1. The goal of any antireflux procedure is to create enough resting pressure in the area of the lower oesophageal

sphincter to prevent reflux of gastric contents while allowing lower oesophageal relaxation and easy passage of food.

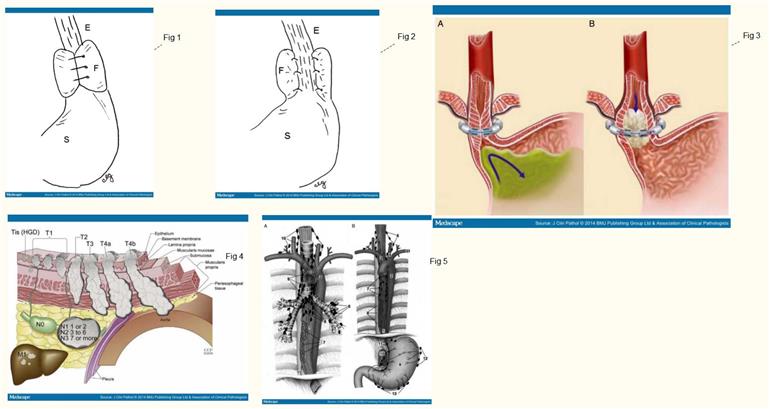

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 1.

Nissen fundoplication (360° wrap). Oesophagus (E), Nissen fundoplication (F) and stomach (S).

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 2.

Toupet fundoplication (270° wrap). Oesophagus (E), Toupet fundoplication (F) and stomach (S)

(Enlarge Image)

09 January 2015 00:48

G E R D Page 1

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 3.

The LINX® device in the closed position (A) and in the open position (B).27

When a patient is found to have Barrett's oesophagus on biopsy, the most important question to be answered by the pathologistis 'is low-grade or high-grade dysplasia present?'. Surgical management of the patient will be determined by this information, so it is mandatory thata second evaluation by another pathologist with expertise in gastrointestinal disease be performed to verify the findings.[28,29]If a patient is found to have Barrett's oesophagus without dysplasia then most gastrointestinal societies recommend surveillance every 3–5 years (Table 1).[29]If a patient is found to have Barrett's oesophagus with low-grade dysplasia, the general recommendation is to repeat biopsies within 2–6 months. If low-grade dysplasia is still present, then biopsies are repeated. Endoscopic surveillance for Barrett's oesophagus presents a significant economic burden to society andcontinues to be a source of controversy without a universally agreed upon treatment algorithm.

Prior to the advent of oesophageal ablative therapy, oesophagectomy was recommended for Barrett's oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Currently, RFA and endoscopic resection (ER) are similarly effective therapies which spare patients the morbidity and mortality of oesophagectomy.[30–36]In RFA, a special device is inserted with an endoscope, and radio-frequency energy burns the diseased oesophageal lining leaving an ulcer. The ulcer will then heal with normal oesophageal epithelium.[34]There are many different techniques for ER but the most common is the resection cap technique. During endoscopy, saline is injected to lift the target lesion off the submucosa, and the lesion is sucked up into the endoscope with a special transparent cap. This 'pseudo polyp' is then resected from the underlying tissue using a snare and electrocautery.[3,31]ER, unlike RFA, is a diagnostic procedure that provides a specimen from which tumour depth, differentiation and lymphovascular invasion can be determined. While the immediate morbidity is lower, RFA and ER require careful long-term follow-up since the rate of recurrence is slightly higher than with oesophagectomy.[37,38]Guidelines on the optimal management of patients with Barrett's oesophagus have recently been published by the British Society of Gastroenterology.[28]In general, it is recommended that Barrett's patients with high grade dysplasia be managed at tertiary referral centres which have expertise in RFA, ER and oesophagectomy.[28]Additonally, patients with long-segment Barrett's oesophagus (≥8 cm), large hiatal hernia, poorly controlled reflux despite aggressive proton pump therapy and poor differentiation are less likely to have successful endotherapy. These patients should be considered for early oesophagectomy.[32,39,40]

Oesophageal Adenocarcinoma

Invasion beyond the muscularis mucosae is the defining transition point between endoscopic and surgical treatment of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. This is due to the increased risk of lymph node metastases beyond the submucosa. In fact, lymph node status is the only independent risk factor for survival and recurrence.[41–46]While there is no consensus on the best surgical approach, it has been shown that tertiary high-volume centres experience better results with lower in-hospital mortality.[47]

For reference; the current American Joint Committee on Cancer 7th edition staging system for oesophageal cancer is shown in figure 4.

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 4.

7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classifications. T is classified as Tis, high-grade dysplasia; T1, cancer invades laminal propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa; T2, cancer invades muscularis propria; T3, cancer invades adventitia; T4a, resectable cancer invades adjacent structures, such as pleura, pericardium, or diaphragm; T4b, unresectable cancer invades other adjacent structures such as aorta, vertebral body, or trachea. N is classified as N0, no regional lymph node metastasis; N1, regional lymph node metastases involving 1–2 nodes; N2, regional lymph node metastases involving 3–6 nodes; N3, regional lymph node metastases involving 7 or more nodes. M is classified as M0, no distant metastasis; M1, distant metastasis. Adapted from Rice and Blackstone [65].

There are several different types of oesophagectomy. Vagal-sparing oesophagectomy was developed for patients with intramucosal oesophageal cancer who did not need the extensive lymphadenopathy of a standard oesophagectomy.[48]By avoiding the extensive lymph node dissection, the vagal nerves are spared and patients experience less gastrointestinal side effects, such as dumping and early satiety.[49]The development of RFA and ER has largely supplanted this surgical technique, but it is still indicated in patients who require an oesophagectomy, but do not need an extensive lymph node dissection.

In patients with advanced locoregional tumours (invasion through the submucosa) extensive lymph node dissection should be performed.[50]Our preferred surgical approach is the en bloc oesophagectomy.[51]An en bloc oesophagectomy requires removal of the oesophagus and surrounding tissue as an en bloc specimen to maximise the number of lymph nodes removed. Some surgeons prefer an Ivor–Lewis approach which requires only two incisions (thoracic and abdominal), but our preference is a three-incision approach (right thoracotomy, laparotomy and cervical incision). This allows us to perform a cervical oesophago-gastrostomy. A right thoracotomy is performed first. This allows mobilisation and dissection of the oesophagus, division of the azygous vein and surrounding lymph nodes, ligation of the thoracic duct and a mediastinal lymphadenectomy (figure 5). This specimen is bordered laterally by mediastinal pleura, anteriorly by the pericardium and membranous trachea and posteriorly by the aorta and vertebral bodies. During dissection, both the right and left vagal nerves are sacrificed. Once the oesophagus and its surrounding tissue are sufficiently mobilised, the thoracotomy incision is closed and the patient is repositioned for the abdominal portion of the operation. A midline incision (laparotomy) is performed to allow dissection of the lymph node-bearing tissue surrounding the porta hepatis, retroperitoneal tissue overlying the pancreas and splenic artery, and the gastrocolic omentum.The gastroepiploic vascular arcade of the stomach is preserved and the short gastric vessels are divided near the splenic hilum. The coronary vein and the left gastric artery are ligated at their origin. The cervical oesophagus is then exposed in the neck through a surgical incision made along the anterior border of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle. The strap muscles of the neck are divided. A dissection plane is created between the carotid sheath laterally and the trachea medially to expose the oesophagus at the prevertebral fascia. The thoracic inlet is then developed, and the oesophagus is divided as low as possible. The oesophagus and tumour are passed inferiorly through the chest into the abdomen.[51–53]

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 5.

(A) Ventral view of the mediastinum including the oesophagus (1), thoracic aorta (2) and trachea (3). (4) Right principal bronchus; (5) left principal bronchus; (6) bronchopulmonary LNs; (7) juxtaoesophageal pulmonary LNs; (8) inferior tracheobronchial LNs; (9) superior tracheobronchial LNs; (10) anterior mediastinal LNs; (11) thoracic duct. (B) Ventral view of the mediastinum included oesophagus (1) and thoracic aorta (2). (3) Brachiocephalic trunk; (4) left common carotid artery; (5) left subclavian artery; (6) anterior mediastinal LNs; (7) juxtaoesophageal pulmonary LNs;(8) prevertebral LNs; (9) anterior facies of the stomach; (10) coeliac trunk LNs; (11) gastric sinistri LNs; (12) pancreatico-colic LNs; (13) gastro-omental LNs. LNs, Lymph nodes. Adapted from Broering et al[66].

Trans-hiatal oesophagectomy was developed in order to minimise the morbidity of a thoracotomy. In this procedure, only a midline laparotomy and left

G E R D Page 2

Trans-hiatal oesophagectomy was developed in order to minimise the morbidity of a thoracotomy. In this procedure, only a midline laparotomy and left neck incision are used. Through a laparotomy, lymph node dissection across the diaphragmatic hiatus is similar to the en blocoesophagectomy. However, removal of the lower mediastinal lymph nodes is limited. Most of this operation is performed under direct vision through the widened oesophageal hiatus. The remainder of the upper oesophageal resection is carried out with blunt hand dissection. The vagal nerves are divided. Once the oesophagus is completely mobilised, the surgical specimen is removed and a cervical oesopahgo-gastrostomy is performed as described in the en bloc oesophagectomy section.[52,54]

Once the oesophagus is removed by one of the three techniques described above (vagal sparing, trans-hiatal or en bloc oesophagectomy) reconstruction to re-establish continuity between the cervical oesophagus and the stomach is performed. A gastric tube is created using a linear stapler along the lesser curve of the stomach. The gastric blood supply is based on the right gastric and gastro-epiploic arteries (figure 6).[55,56]Although, the gastric conduit is more commonly used due to its superior blood supply and ease of use, the colon and small bowel have also been used as an oesophageal replacement when the stomach is unavailable.[57]Since vagotomy is performed, a pyloromytomy is done to promote gastric emptying. A feeding jejunostomy is indicated to allow enteral feeding in the early postoperative period while the surgical anastomoses are healing. Patients who have undergone oesophageal reconstruction, either with a gastric or colonic interposition, and who survive their cancer, do well long-term with good alimentary satisfaction and quality of life.[58,59]

(Enlarge Image)

Figure 6.

Tubularised stomach. Note, the oesophagus must be resected at least 5 cm from the tumour-free margin. Adapted from Chernousov et al[67].

Summary

GERD and its potential complications of Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma are now the most important disease processes for oesophageal surgeons. A major impact on this disease will likely come from the development of cost-effective screening and diagnostic modalities which identify patients who are at risk for developing oesophageal cancer. The surgical approach to Barrett's oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma will continue to evolve in response to advances in ablative therapy and ER. The role of the pathologist, with expertise in the diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus, will become more prominent as we better define the histological predictors of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. A collaborative effort between pathologists and surgeons is essential in determining the timing and best approach for interventional therapy.

ATTRIBUTION :-

Correction notice

The article type of this article has been changed since published Online First.

Contributors

CLG is responsible for the concept of the work, its design, drafting and final approval. She is responsible for all aspects of the work. PMM contributed to the intellectual content, revision and final approval of this manuscript.

Competing interests

None.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

J Clin Pathol.2014;67(10):913-918.©2014BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & Association of Clinical Pathologists

All material is protected by copyright, Copyright © 1994-2015 by WebMD LLC. This site also contains material copyrighted by 3rd parties.

From <medscape.com/viewarticle/83...

G E R D Page 3