This is chapter 17 of a book I published in 2015, "A Different Way of Looking at Parkinson's. Almost 20 years of experience with my father's disease (1994-2012)" (only in Spanish). Although we have learned a lot more since that year, I think it can still be useful to most sufferers and family members. And with that intention I have translated it from the original Spanish to English and share it with everyone.

I ask you to excuse any possible errors in the translation.

CHAPTER 17.

I DREAM OF THE REVOLUTION THAT MUST COME, OF A WORLD WITHOUT PARKINSON'S.

"What is heresy today often becomes tomorrow's orthodoxy.".

José Luís López Aranguren

"We cannot solve problems by thinking

in the same way as when we created them".

Albert Einstein

- This chapter is a space to dream of a world without Parkinson's, to speculate with the freedom and daring of imagination, of intuition. Parkinson's is still a challenge. Although much progress has been made, we can by no means be satisfied. I know few senior physicians and patients who are.

Neither my father nor I were doctors or specialists in neurology, but from what we experienced, what we read, what we talked to other patients, what our doctors told us, we came to have a wealth of important information about some aspects of the disease, much of it of a practical nature. In much the same way that miners sift the earth with sieves in search of gold nuggets, so it happened to us.

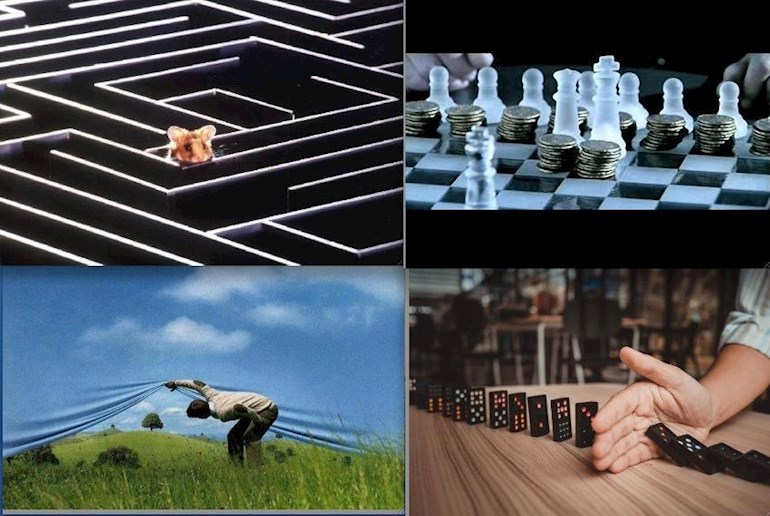

The Revolution in the world of Parkinson's affects all its "actors" and perhaps the way to solve the "puzzle" is Integrative Medicine (the best of Official Medicine and Complementary and Alternative Medicine, to put it simply), multidisciplinary teams led by a neurologist, with a gastroenterologist, an expert in epigenetics and nutrition ... I do not know. Unfortunately it still seems only a dream. -

17.1. Are we at a dead end?

"Revolutions take place in dead ends".

Bertolt Brecht

The disease I knew in 1994 has almost nothing to do with the one I know today. Our experiences and both stories, the experience of our own and the study of the general history of the disease, gave us a new global vision, to the point that they seem like two very different things. In fact, we could speak of two "different" diseases when referring to Parkinson's before and after starting treatment.

I have been observing and reflecting on the world of Parkinson's for 20 years (in a sense, a "microuniverse" that feeds back on itself), both in the part that has affected me personally as a son and caregiver, and in the part that attracts me as a professional historian and digital journalist, and the conclusions I reach in 2015 are the following, and I state them with humility and respect, but with clarity:

1. despite the increasing means, in money, in number of researchers, in neuroimaging techniques, in drugs pending trials, etc.; in the last almost 50 years, since the American FDA approved in 1970 the use in humans of L-dopa, there have been no revolutionary changes in Parkinson's treatments, and if there have been, they are not perceived as such by most of the sufferers with whom I have spoken. But those who have had the disease for many years generally think this way. The more recent sufferers are still fascinated by the "miraculous" effects of medication in the early years.

2. Statistics and forecasts for the coming decades speak of the number of cases doubling and even tripling in the industrialized world (Dorsey 2007). This is usually related to the aging of the population, but I do not believe this to be entirely true, since the increase in cases is not directly related to the increase and aging of the population. In this sense, it also points to the existence of an increasing percentage of younger patients than usual.

3. There is an abyss, an increasing step in the group of patients, depending on the country in which they live, their economic, social and cultural situation, their age, etc. Generally, the younger, wealthy and educated opt for complementary and alternative therapies and treatments much more frequently than the older, poorer and less intellectually prepared.

4. When a sufficient volume of studies is compiled (as Werbach, González Maldonado, Marsden, Micheli or Hurni do) and observed over a prolonged period of time, points of coincidence become evident that go unnoticed at first. Many of the more or less orthodox studies published in scientific journals point in one direction: orthodoxy leads to heterodoxy or to the "heresy" that Parkinson's disease could be a multifactorial syndrome produced directly (by lack of vitamins, minerals, amino acids, enzymes) or indirectly (by lack of sufficient protection against toxins), by deficiency and subclinical disorders (which do not manifest clinical deficiency symptoms but produce damage in the medium and long term).

The role of glutathione, vitamins B1, B2, B3, B6, B9 or B12, magnesium, vitamin D, good intestinal flora, seems to be beyond doubt.

Looking back over these two centuries of modern knowledge of Parkinson's disease, my father and I wondered if Medicine and Neurology had not partly missed the mark, if this super-specialization (as we saw it) was not taking us further away from our objective and if everything would not be simpler? Even my father sometimes thought that the adverse effects of the medication were worse than the original disease itself (this is something he and other patients we met over the years felt).

People outside Parkinson's, newly diagnosed or early Parkinson's patients and their families often have a somewhat unrealistic view of the disease.

17.2. A global and different vision of "Parkinson's diseases".

This concept of "Parkinson's diseases" I came to know thanks to the book "Parkinson's and stress", by Dr. Gonzalez Maldonado.

My father, perhaps exaggeratedly, sometimes referred to his disease as the "disease of (James) Parkinson, but of Antonio Márquez Campos", because he felt that it was something that merged so closely with his way of being and living, that it was a different disease in each patient, even changing in him over the years.

Since James Parkinson described "paralysis agitans" in his 1817 book (later Parkinson's disease), almost two hundred years ago, there have been some advances in the symptomatic treatment of the disease, but hardly any in its prevention and none in its cure.

Very worrying statistics and forecasts.

As we have already mentioned, according to the latest forecasts, Parkinson's cases are expected to double and even triple in the coming decades (and not proportionally to the increase in the volume of the population or to its greater life expectancy or aging). Then there are "modern" factors that have triggered the incidence/prevalence of the disease, especially in populations exposed to the pollutants and dietary habits of industrial society, for example the differences between urban and rural areas in Taiwan, in terms of Parkinson's cases (Chen 2009). Areas of the same city more exposed to pollution from manganese alloy factories in Brescia, Italy (Lucchini 2007) or in rural areas more exposed to pesticides (Amish in North America, high rates in the state of Nebraska). Manganese inhibits (prevents, hinders) the hydroxylation of tyrosine into dopa (dopamine precursor).

These forecasts and the current reality in which chronic and neurodegenerative diseases have become an authentic plague, show a profound failure as societies in relation to health maintenance and disease prevention, despite the fact that seeing what we have before our eyes is very difficult and we seem to live in an artificial bubble, in which we believe that no era enjoyed as much health as we do (which is, to say the least, debatable).

In both healthy and sick people there is a "blindness" and resistance to making changes towards a healthier lifestyle. One of the paths towards this improvement in the general health of the population could be the recovery of some old healthy habits (fasting, purging, rest, sun, recipes and healing formulas, medicinal plants), when they are supported by modern scientific knowledge and authorized by the physician.

The consumption of psychotropic drugs, the increase in the use of drugs and alcohol among the youngest, junk food, the harmful side of technology, mean that for the first time in a long time, children may have worse health than their parents and grandparents (as has happened in Okinawa, for example).

The human cost in suffering for the sick and their families is unacceptable. The economic cost to the various countries (for their citizens, of course) will soon be unsustainable.

I would not know if the war against Parkinson's disease is being won...

Dogmas about Parkinson's.

"A new scientific truth does not usually impose itself by convincing its opponents

its opponents, but rather because its opponents gradually disappear

gradually disappear and are replaced by a new, familiar generation

by a new generation familiar with the new truth

with the new truth from the beginning.

Max Planck, father of Quantum Physics.

"Science is believing in the ignorance of scientists."

Richard Feynman, American physicist.

We are still living, in part, on late 19th and early 20th century notions of health and disease.

Feynman's and Max Planck's sentences (and there are hundreds of others of the same level), shed much light on the problems that nowadays hinder real progress in the fight against Parkinson's disease.

The "dogmas" about the brain, the central nervous system and Parkinson's are being called into question, thanks to Science. Doubting is the essence of scientific thinking.

The first to be demolished was the one formulated by the wise Santiago Ramón y Cajal about the progressive death of neurons and the impossibility of creating new neurons in adults (neurogenesis). Today it is known that the brain is capable of regenerating itself thanks to the creation of new neurons in the hippocampus and other regions of the brain, and to neuroplasticity (physical exercise, positive thoughts, omega 3 EPA and DHA, etc.).

Another dogma that seems to be about to fall, if the research of Dr. Bernardo Sabatini, neurobiologist, is confirmed, is that of the "exclusive" role of dopamine in Parkinson's disease. It seems that GABA (the main inhibitory neurotransmitter) would play a role of similar importance to that of dopamine (almost 50%).

When a person believes that 70 to 80% of the neurons in some parts of the brain have already died when the first symptoms of Parkinson's disease appear, it is very difficult to be optimistic and to muster the will to fight.

Some worrying issues.

The high percentage of misdiagnosis due to its difficulty in the initial stages, the delay in diagnosing the disease, which can take up to 4 years on average, the use of drugs that produce and aggravate Parkinsonisms (called PIF), the lack of prevention campaigns based on current knowledge (green tea, coffee, turmeric and pepper, etc.), and the lack of a prevention campaign based on current knowledge (green tea, coffee, turmeric and pepper), coffee, turmeric and black pepper, flavonoids, folic acid, vitamin D) through the media (movies, TV series, prime time programs), make the future an unknown and, sometimes, not very hopeful. But this is just an appearance.

My father once told me -with some bitterness- that if scurvy had not been investigated more than a century ago, today we would be speculating on whether it is caused by genes, some environmental toxicant or a virus, and it would be treated with corticoids and coagulants instead of with fruits rich in ascorbic acid or vitamin C (lime, lemon) as Dr. James Lind did.

Perhaps, in addition to continuing research, we should turn our eyes more to the past, change our mentality and review everything we have unlearned in these years and relearn everything we had disregarded and marginalized.

Fortunately, Neurology is becoming more and more aware of physical exercise, stress, nutrition, music, etc.

The human brain: an unknown universe?

Only a deep feeling of admiration can be felt by anyone who ventures into the study of the human brain (even at an informative level), of the rest of the central nervous system, of the incredible complexity of a single neuron and, even more so, of 100 billion neurons, over an area of 100,000 million neurons. billion neurons, over a trillion glial cells, trillions of connections or synapses, trillions of bioelectrical and chemical reactions in a second interacting with each other and with the environment... an unimaginable number of potassium and sodium channels and pumps in each neuronal membrane, trillions of mitochondria, etc.

The famous Italian neuroscientist Rita Levi Montalcini let her passion for neuroscience, but also her bewilderment at the wonders and complexities of the human brain, shine through in every interview she was given.

The secrets and mysteries of the brain remain hidden. In fact, almost everything about this disease remains a mystery: what it is, what causes it, how to prevent it, how to cure it, or even how to turn it into a chronic but non-degenerative ailment, if that were possible.

Or maybe not?

The question my father and I have been asking ourselves all these years is whether all this gigantic world of research translates into real and concrete advances in the lives of people affected by chronic and degenerative diseases of the brain and nervous system.

Until recently, it was believed that neurons died inexorably. Today it is known that new ones are created every day in a region of the brain called the hippocampus and in the striatum (Eriksson 1998, Frisen 2013, Ernst 2014).

Until recently we thought that the pineal gland was useless, today we know that it produces the all-important hormone melatonin.

Until recently we thought that the nervous system surrounding the gut hardly decided anything except digestive processes and today we begin to sense its importance as a "second brain" connected to the limbic brain, the brain of emotions, through the vagus nerve. And it produces 95% of serotonin and 50% of dopamine, with about 100 million nerve cells. Even the intestinal flora plays a very important role in the mind, as we already know.

(continued in the second and last part)