March 2014

Dry and sunny at last. In the middle of planning this year’s ‘Ten Topics’ meeting. This annual two-day postgraduate meeting focuses in particular on lupus, Hughes syndrome and related clinical topics.

This year, our London meeting will be held at the glorious Glaziers’ Hall, next door to London Bridge Hospital on Thursday and Friday, the 3rd and 4th of July. The meeting is so popular that ‘satellite’ Ten Topics meetings are held regularly in Barcelona, the Far East (so far in Manila, Hong Kong and Singapore), the Middle East (Beirut) and South America (Mexico and Buenos Aires). As well as the London Lupus Centre team, this year’s speakers come from all over the UK, as well as from Israel and Spain.

This year we have broadened the programme to cater for interested GPs. If your own doctor is interested, do ask him or her to contact Sandy Hampson, here on 020 7234 2322, or visit our websites on tentopics.com or londonlupuscentre.com.

Talking of meetings, I now travel much less than my younger colleagues, but this month, in France, was a ‘must’ – the biennial international congress on autoimmunity, organised as always by my friend Yehuda Shoenfeld. I personally regard this as the very best medical meeting going. Not only as it is well organised, but, uniquely, it covers all aspects of immunity ranging for cancer, to multiple sclerosis, from vaccination to Hughes syndrome.

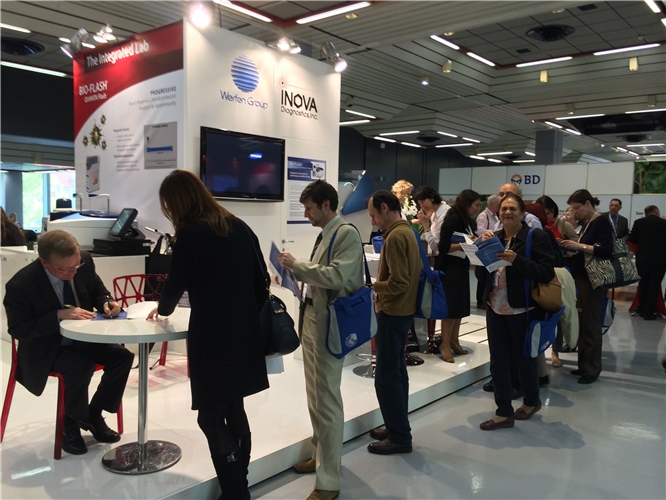

INOVA, one of the major companies developing tests for many of these diseases, has put together three years’ worth of my monthly ‘patient of the month’ blogs into a book. I was asked whether I would sign copies of the book during the meeting. In the event, it was amazing – on the second day of the congress, a queue snaked round the central area of the congress exhibition – over 200 signed! Colleagues from countries as far apart as Russia, Australia and the USA highlighting the clinical interest in this syndrome. The book, Clinical Case Studies is available from the Hughes Syndrome Foundation: hughes-syndrome.org/get-inv...

Patient of the Month

“Dear Doctor Hughes,

Mrs A.B. has recently suffered a stillbirth in the 8th month of her pregnancy. She had previously suffered two early miscarriages at three months and three and a half months respectively. Although her lupus anticoagulant (LA) and anticardiolipin tests (aCL) are negative, I wondered whether Hughes syndrome might be an underlying cause……………..?”

We re-tested her. Our own LA and aCL tests were also negative, but interestingly, another (related) blood test, called anti-PE was in fact positive.

Despite her past history, the patient is planning another pregnancy (for certain to be treated with heparin and aspirin!). I will keep you posted.

What is this patient teaching us?

The G.P. was right. Hughes syndrome is more than likely to be the underlying problem. The syndrome is now recognised internationally as the commonest, treatable cause of recurrent miscarriage.

One would have assumed that simple anti-phospholipid (aPL) testing would now be routine in all pregnancies – or, if not, certainly after a miscarriage. Unfortunately not - the reason being that there are, of course, many known causes of miscarriage. It is therefore widely accepted that routine aPL testing is only required after three miscarriages! I can see the (economic) arguments for this, but I am fighting to encourage more widespread earlier testing.

For example, in my address last year to the world congress on anti-phospholipid antibodies (published in April - in the medical journal LUPUS (2014, Volume 23, pages 400-407) – lup.sagepub.com/content/23/... I proposed a simple three question screening test for possible Hughes syndrome to be included in the initial pregnancy visit:–

1) Do you suffer from migraine?

2) Have you ever had a thrombosis?

3) Do you have any family members with auto-immune diseases (thyroid, rheumatoid, lupus, Hughes syndrome, multiple sclerosis)?

It has not yet been fully put to the test, but I’m willing to bet that it will help to hone down on those at risk of pregnancy loss. (Significantly, Mrs A.B. had a younger sister with Hashimoto’s disease – low thyroid).

Sadly, Mrs A.B. had not only suffered two early miscarriages, but went on to suffer a late pregnancy loss – a stillbirth – described in a Times of London leader last year as one of the greatest tragedies known to mankind - “the stillbirth scandal”.

A recent study by colleagues in America reported that mothers with aPL-positive pregnancies had a 3 to 5-fold increased odds of stillbirth. In Mrs A.B.’s case think of what aPL testing prior to her second pregnancy might have achieved!

Mrs A.B.’s case also teaches us a second lesson – the fact that conventional tests for Hughes syndrome can be negative.

Tragically, some doctors, unknowingly, dismiss such patients as not having the syndrome! One probable explanation for ‘sero-negative Hughes syndrome’ is that in cases such as Mrs A.B., our current tests are insufficient. A number of centres (and kit-testing companies such as INOVA) are actively looking at newer tests in cases of sero-negative cases.

For me, this is arguably the single most important topic of clinical research in Hughes syndrome at this time.

Let me explain why.

Not a week goes by without my seeing at least two or three patients who have classical Hughes syndrome (and who respond to treatment) in whom aPL tests are

negative. And when one looks into it, the majority have ‘made it’ through the system because they have had a sister, cousin, mother or other relative with the syndrome – enough to point them in the direction of the G.P. or the internet.

Think of how many cases we are missing. If, for example, one were to add up the numbers of patients in the UK with (young) stroke, with migraine, with balance problems, with MS, with unexplained angina – and even if Hughes syndrome accounted for 1% of each - the numbers of potentially treatable cases out there could be considerable.

Reference:

Hughes GRV. The Stillbirth Scandal. LUPUS 2013. Vol 22. Pp759-760