Hypertension is a frequent subject here.

This research paper provides a lot of discussion! I started reading and thought it might be of interest - but have not yet reached the end.

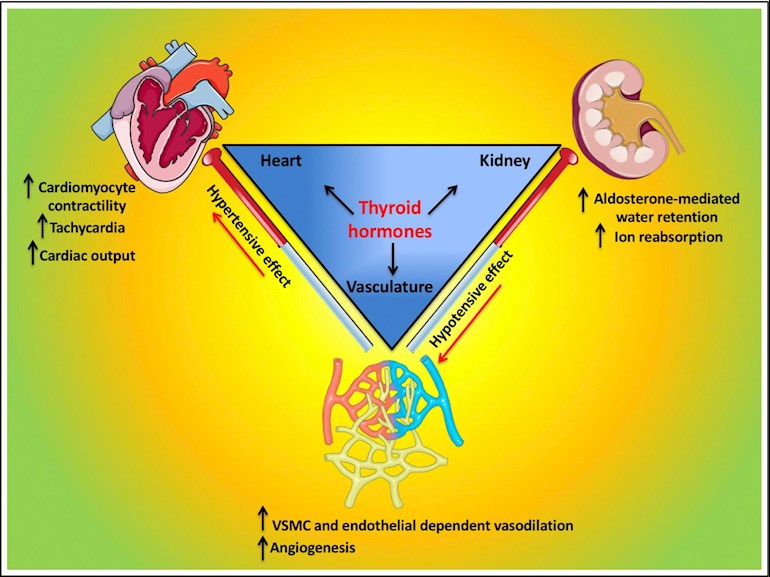

Thyroid hormones regulate both cardiovascular and renal mechanisms underlying hypertension

Stanislovas S. Jankauskas PhD, Marco B. Morelli PhD, Jessica Gambardella PhD, Angela Lombardi PhD, Gaetano Santulli MD, PhD,

First published: 29 December 2020

Stanislovas S. Jankauskas, Marco B. Morelli and Jessica Gambardella contributed equally to this study.

Physiologically, thyroid hormones are able to affect the fundamental determinants of blood pressure (BP): cardiac output, peripheral vascular resistance, and kidney function (Figure 1). The thyroid-mediated fine orchestration of cardiac contractility, vascular tone, and renal homeostasis confers to the thyroid gland a key role in the pathophysiology of hypertension. Indeed, BP is altered across the entire spectrum of thyroid diseases.1However, the effects of thyroid disorders on BP are very intricate, mirroring the multifactorial and disparate actions of thyroid hormones on cardiovascular system and metabolism. In fact, if on one hand thyroid hormones increase contractility, tachycardia, and basal metabolic rate, which are positive regulators of BP, on the other hand they are able to decrease systemic vascular resistance, thereby lowering BP. Ergo, the balance between these opposite actions is eventually able to achieve an optimal regulation of BP, and modifications in thyroid hormones availability, both hypo- and hyperthyroidism, can alter this fine equilibrium. A wide and consistent literature is available on the association between thyroid disorders and hypertension.2However, only few studies have explored the relationship between BP and thyroid hormones in healthy subjects, in order to understand whether different levels of thyroid hormones, within a physiological range, can reflect changes in BP. In this context, in the current issue of the Journal, Jamal and colleagues offer their elegant investigation conducted on 691 healthy subjects.3The authors elegantly show that in a physiological context, augmented serum levels of triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4) are associated with an increase of both peripheral and central BP. A strength of the study is denoted by the choice to measure central BP, which is suggested to be a more reliable prognostic marker in cardiovascular disorder compared to conventional brachial cuff BP.4The authors open the scenario for a potential role of serum level of thyroid hormones as predictor of central BP, and therefore a powerful prognostic factor of hypertension and cardiovascular complications. Of course, further studies are needed to verify and better understand the proposed relationship, even to enlarge the sample population. Moreover, in future studies it could be interesting to perform a time-course assessment of thyroid hormones levels (which usually oscillate in the same subject) evaluating their effects on BP variation. Indeed, a circadian rhythm has been demonstrated for triiodothyronine (T3), with a periodicity that lags behind thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).5, 6Another aspect that needs to be further examined is the potential role of the effects of T3 and T4 on the intricate interaction between cardiovascular and renal systems.7-9To better characterize the complex context in which the study performed by Jamal and colleagues3fits, here we propose a summary of the central mechanisms by which thyroid hormones can affect cardiac output, vascular resistances, and kidney function. We also summarize the results of the most recent clinical studies focused on the relationship between thyroid hormones and hypertension.