In 2014, Sharon Peacock, a professor of microbiology at the Unviersity of Cambridge, wrote an important piece in Nature, first page shown below, advocating sequencing as a standard of care to rapidly determine the causative pathogen and direct appropriate therapy—since the sequence can reveal mutations that confer resistance to antibiotics. She wrote: “Microbial sequencing should be done as close to the patient as possible.” To achieve the best outcome, the need for speed to crack the case and initiate the right treatment cannot be emphasized enough.

This is the opening paragraph from Dr Eric Topol's article A Culture of [Blood] Cultures in Ground Truths. erictopol.substack.com/p/a-...

Snips:

In that same year, 2014, we saw the life saved of Joshua Osborne, who had sequencing of his cerebrospinal fluid finally establish (within 48 hours) the elusive diagnosis of leptospirosis after many weeks of an extensive battery of tests, including a brain biopsy, that had failed to establish the cause of his encephalitis. About half of such infections of the brain are left undiagnosed with current approaches which include lab screening for a variety of pathogens and culture of the cerebrospinal fluid.

:

Today when a patient presents with possible sepsis we draw multiple blood cultures and wait a few days before the results come back with a possible pathogen and readout for antibiotics that may be useful. The patient is bombarded with “empiric, broad spectrum antibiotics” to cover all the bacteria that are thought to be potentially causal, with implicit acknowledgement that viruses and other pathogens (fungi, parasites) won’t be covered by the antibiotic cocktail. That “blitzkrieg” cocktail, which may not even be directed to the underlying pathogen, has potential toxicity for the kidneys and other vital organs, and is typically continued until the cultures come back. All too often the cultures are negative, not revealing a/the pathogen, or show a contaminant, so, dependent on the patient’s clinical condition, the cocktail is continued for a full course of several days or longer. More potential for adverse effects of potentially misdirected antibiotics.

(This has been my experience several times now when I've been admitted for febrile neutropenia or some unknown infection and I know from other posts, that this is indeed the standard approach as Dr Topol states.)

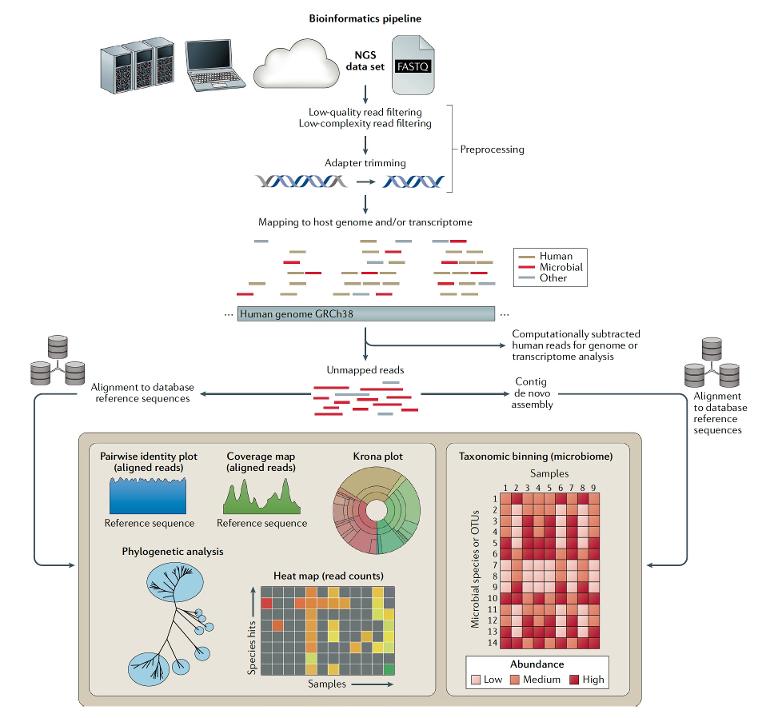

In contrast, “clinical metagenomics” as the field is known, takes an agnostic approach as to what is the causative pathogen. As shown in this excellent review, sequencing can be performed on any body fluid or tissue and there are several steps required, besides the sequencing, that include library preparation and bioinformatic analysis. There is no assumption about the bug—many cases successfully diagnosed by this technique would have been unthinkable pathogens, like an ameba or tuberculosis. The sequence tells the story in place of a clinician’s intuition for what might be the cause of infection.

:

While the opportunities here are extraordinary but the field is unmoved, UCSF, a pioneer in this movement, has already gone on beyond pathogen sequencing. They recently published the integrated use of metagenomics of the pathogen with host gene expression in critically ill patients, which identified 99% of confirmed sepsis cases, and the ability to separate out sepsis from non-sepsis etiologies. (See attached graphic, plus emphasis is mine - Neil)

One big reason we haven’t seen clinical metagenomics take off is our culture, which gets me back to the title of this post. We’ve been doing blood cultures for many decades (7 or more), and using broad-spectrum antibiotics (which have undoubtedly contributed to the crisis of antibiotic resistance) for many decades, and waiting for multiple days per patient for many decades. There’s considerable resistance to change in medicine, despite so many alluring aspects of this technology.

The bottom line: this can be done, but we’re not doing it. There appears to be no drive or incentive to change or adopt this technology for routine medical practice. Meanwhile, sepsis is a leading cause of death—it accounts for 1 of 5 deaths globally—about 11 million deaths in 2017. Patients and their families don’t know about this technology, but if they did, and started clamoring about it, we might begin to see some traction. I keep thinking of how many lives we could save (and could have saved) if only we responded to the charge in Peacock’s 2014 editorial.

This is an unlocked post.

healthunlocked.com/cllsuppo...

Neil

), so good places to have shorter stays than the 5 weeks it took for me to recover!

), so good places to have shorter stays than the 5 weeks it took for me to recover!