An easy read about a complex subject.

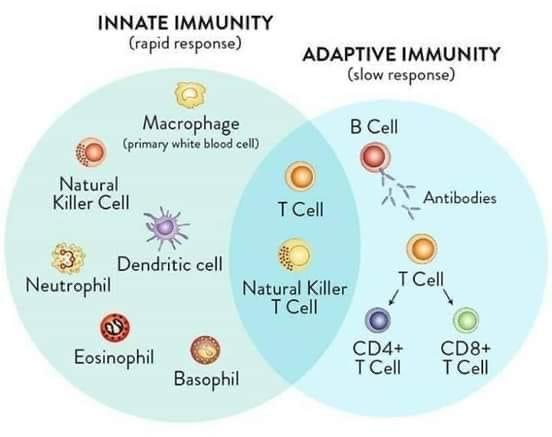

Immunity is a matter of degrees, not absolutes and that lies at the heart of many of the COVID-19 pandemic’s biggest questions. Why do some people become extremely ill and others don’t? Can infected people ever be sickened by the same virus again? How will the pandemic play out over the next months and years? Will vaccination work?

The new coronavirus seems to rely on early stealth, somehow delaying the launch of the innate immune system, and inhibiting the production of interferons—those molecules that initially block viral replication. “I believe this delay is really the key in determining good versus bad outcomes,” says Akiko Iwasaki, an immunologist at Yale. It creates a brief time window in which the virus can replicate unnoticed before the alarm bells start sounding.

Immune responses are inherently violent. Cells are destroyed. Harmful chemicals are unleashed. Ideally, that violence is targeted and restrained; as Metcalf puts it, “Half of the immune system is designed to turn the other half off.” But if an infection is allowed to run amok, the immune system might do the same, causing a lot of collateral damage in its prolonged and flailing attempts to control the virus.

This is apparently what happens in severe cases of COVID-19. “If you can’t clear the virus quickly enough, you’re susceptible to damage from the virus and the immune system,” says Donna Farber, a microbiologist at Columbia. Many people in intensive-care units seem to succumb to the ravages of their own immune cells, even if they eventually beat the virus. Others suffer from lasting lung and heart problems, long after they are discharged. Such immune overreactions also happen in extreme cases of influenza, but they wreak greater damage in COVID-19.

Lots more to read here (about a 10 minute read): theatlantic.com/health/arch...

Jackie