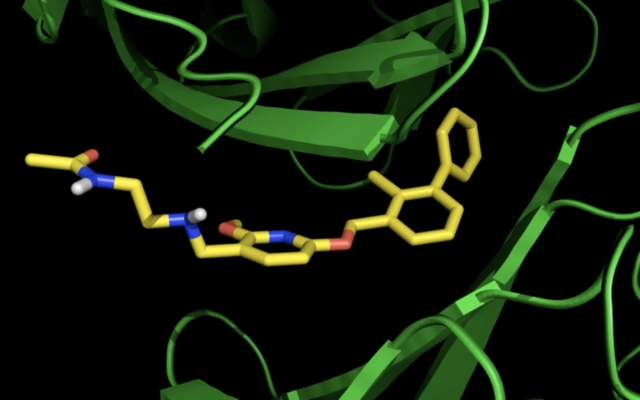

A computer-generated image of the synthetic cancer-fighting molecule developed at Tel Aviv University encountering proteins that inhibit the immune system. After encountering the proteins it reprograms them, to enable the immune system to fight the tumor. (courtesy of Tel Aviv University)

Cancer patients currently need to visit a hospital for treatment; Israeli-Portuguese research could change this, scientists say, although potential drug years away

By NATHAN JEFFAY

Today,

Israeli scientists are developing an oral immunotherapy for cancer, and say they expect it to be the first such drug to become available for use.

Today there are some oral immunotherapy treatments for allergies, but not cancer immunotherapy, which is delivered through different means. It’s given most commonly straight into the vein — intravenously.

This means that cancer patients need to endure a hospital visit to receive immunotherapy.

The main barrier to oral doses, which could be taken at home, is that the antibodies which form immunotherapy drugs don’t survive in the gut.

Researchers at Tel Aviv University, together with colleagues at the University of Lisbon, have developed a synthetic molecule that they say does the job of antibody-based immunotherapies. Theirs is one of several attempts underway at oral cancer immunotherapy.

The Israeli-Portuguese team published a peer-reviewed study on their breakthrough in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer.

The article revealed that the team successfully tested their molecule in vitro as well as on a human tumor in a special lab model.

A potential drug is years away, as further development is needed followed by human testing, but one of the researchers, Prof. Ronit Sacthi-Fainaro, head of Tel Aviv University’s Center for Cancer Biology Research, told The Times of Israel that the theoretical research is significant.

“This is important, as the new molecules have many advantages. They can be given orally, are cheaper to produce than antibodies, and penetrate more areas of the tumor than antibodies can reach,” she said.

Immunologists who aren’t involved in the research say it is promising.

“This is an exciting study by pioneering groups, in line with some others, showing the promises of oral immunotherapy against cancer,” Prof. Cyrille Cohen, head of the immunology lab at Bar Ilan University, told The Times of Israel.

“I look forward to seeing its implementation in clinical trials that will compare the efficacy in cancer patients of these new drugs to current antibodies. If successful, I have no doubt that it will fast forward another revolution in cancer care,” Cohen said.

Illustrative image: A cancer patient receives immunotherapy. Today, oral immunotherapy for cancer isn’t available. (AP Photo/Elaine Thompson)

Immunotherapy works by telling the immune system what doctors want it to do in order to fight cancer. All too often, proteins in the body instruct immune cells — called T-cells — not to attack cancer.

Doctors have developed special drugs to reprogram the immune system — immunotherapy. One of the most popular immunotherapies stops two particular proteins — PD-1 and PD-L1 — from suppressing the immune system.

The molecules created by Satchi-Fainaro and colleagues do the same, encountering the proteins which would ordinarily suppress an anti-cancer immune response and reprogramming them so that the desired immune response takes place. Her team released a computer generated image of the molecules encountering the proteins in question.

The immunotherapy is made from antibodies, which don’t survive the harsh, highly acidic environment of the human gut, are expensive to produce, and are too big to enter some parts of a tumor.

“Antibodies don’t survive the intestinal tract,” explained Satchi-Fainaro. “They get degraded before they reach the tumor. These synthetic molecules, by contrast, have been designed especially to be resilient and not degrade in the gut, which opens up the exciting possibility of giving them orally.”

The synthetic molecules are also far smaller than antibodies.

“Antibodies have difficulty reaching some parts of a tumor, and the problem is their size. They always stay close to blood vessels and therefore can’t reach parts of the tumor that are far from blood vessels,” said Satchi-Fainaro.

“Our molecules don’t have this constraint, and can actually go anywhere in the body, diffusing through the body instead of needing blood vessels to move around.

“It’s a matter of size. Antibodies are 150,000 dalton [a measure of mass] while the small molecules are 500 dalton. And so, antibodies are the equivalent of trucks — needing large roads, or in their case blood vessels, to move around. Small molecules are the equivalent of pedestrians, who can find their way even in the absence of roads, a sidewalk, or even a marked path.”

Satchi-Fainaro believes that synthetic molecules could make immunotherapy more accessible.

Antibody-based immunotherapy requires a complex infrastructure and considerable funds to produce, costing about $200,000 per year per patient.

Synthetic molecules, once in large-scale production, will be cheaper to make and could make immunotherapy available at “a fraction of the cost,” Satchi-Fainaro said.