This is a follow-on from yesterday's post: Research on effectiveness of different face coverings. I'm making a new post because it's long and a bit involved, and of course I want people to read it.

Newdawn posted the results of the Duke University study on face coverings advances.sciencemag.org/con... which is a useful guide for situations where the main effect of the covering is to protect bystanders from transmission of the virus in droplets coughed and spluttered by the wearer. Many people wrongly believe that wearing a mask is mainly to protect themselves.

But what of the wearer's own safety? What about the clinically extremely vulnerable, we who have recently been unshielded? Is there a mask good enough to protect us as we mingle again, out there in the world, with people who may or may not be masked up? Good enough to stop us inhaling virus particles that other folk have simply breathed into the air? The long-held official line, that hand-washing and social distancing was all we needed to keep us safe from Covid19, has been debunked by several studies highlighting the aerosol transmission route. Just read the 10-line summary of this recent article in The Lancet thelancet.com/journals/lanr...

Back to face coverings, let's get one thing straight: the moniker "surgical mask" is misleading. Yes, they are used in certain medical settings, but think Doctor Dolitttle: surgical masks do little to protect the wearer. A heavy-duty "respirator" is much more effective in that respect. Knowing the essential differences between these two kinds of face protection could save your life. cdc.gov/niosh/npptl/pdfs/Un...

Note that a respirator must be close fitting to keep out particles as designed. Because of that and the resistance the fabric offers to air flow, a respirator is more of a chore to wear than a looser-fitting lightweight mask. So when, if at all, is it worth the trouble? Let's first look at what respirators are supposed to do, and then how they measure up in practice.

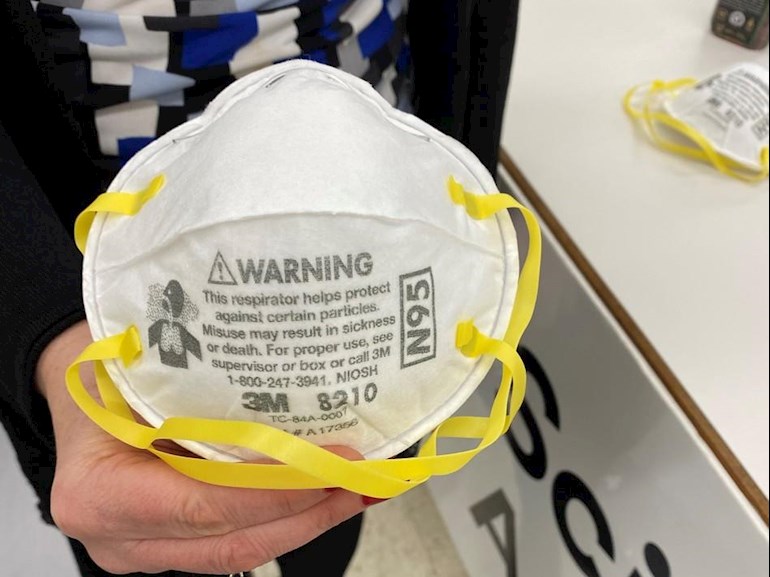

The most widely used classification of respirators is that of NIOSH, the National Institute For Occupational Safety and Health in the USA. The "N" rating of a respirator denotes it is not designed to stop oil particles. For that you need an "R" rated (oil-Resistant) or better still a "P" rated respirator (oil-Proof). The number after the letter, 95/ 99/ 100, denotes the percentage of particulate matter the mask - sorry respirator - is supposed to keep out. Accordingly the Top of the Range would be a P100 respirator, designed to stop 99.97 % of particles including oil.

Hang on a minute: Why is oil resistance important? In the COVID context, it's because virus particles have a lipid coating - they are oily on the outside and could slip through an N-rated respirator more easily than through one P-rated.

And another thing: These respirators were designed primarily to keep out fine particulates in industrial settings. Virus particles are really small, so can't they get though any fabric, oil-proof or not? While a P100 respirator should filter out 99.97 % of airborne particles bigger than 0.3 microns (a millimetre is one thousand microns), that should be no obstacle to a SARS-Cov2 virion measuring ~ 0.1 microns, right? And if an inhaled virion could take just 10 minutes to break into one of your body's cells and 10 hours later a thousand copies break out again, that spells trouble, right? Doesn't that make both respirators and masks redundant, if they only keep out visible water droplets fired directly at you?

Well, it seems not. Research published seven years ago ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articl... measured the performance of NIOSH-approved respirators against aerosolised particles of the virus MS2 (0.03 microns) and found the N95 to be 98 % effective and the P100 to be 99.97 % effective - both well up to their specification for particles ten times as large. Results so inexplicably good, it raises the question: was the test sufficiently rigorous? In the authors' study aerosol particles measured mostly less than 1 micron, while they cited an earlier study which had shown that in a healthcare setting, during the peak of influenza season, most virus particles were in agglomerations larger than 1 micron. A yet earlier study also found the better N95s were up to spec, while surgical masks were easliy penetrated by MS2 virus particles.

Consequently, the 2013 research appears rigorous and inspires confidence that in the real world, NIOSH-approved respirators do protect the wearer from airborne virus particles. Not perfectly, but pretty effectively.

This is the place to add that neither a face mask nor a Top of Range respirator protects the eyes, which provide an alternative entry point for virus. If you want to do the job properly, wear a respirator and glasses, and live with the annoying challenge of taking the one off while leaving the other on, while not touching any part of either that comes into contact with the face!

So we have masks that we can wear to protect others from our coughs and sneezes, and we have respirators that we can wear to protect ourselves and, possibly, others at the same time. I say "possibly" because there are respirators on the market with exhalation valves to make them more tolerable in prolonged use. These valved respirators are just as good at protecting the wearer but no-one else, and a respirator with a forward-facing valve can turbo-charge the wearer's oral emissions, sending them out well beyond 2 metres. healthunlocked.com/api/redi...

Many will argue that a respirator is OTT when in most situations a cheap surgical mask, runner-up in Duke University's test, will do. To an extent I agree. Use Duke's list to pick a face covering mainly to protect others, and in public keep your distance from anyone not wearing such a face covering. But as the economy opens up, new opportunities for transmission open up too, largely because the relaxation of certain control measures is predicated on a) lower prevalence of disease, which on a national basis is true, and b) other control measures getting better, which is highly questionable.

If you are clinically vulnerable and have to leave home to be around other people in an indoor environment, e.g. in an office, a school, a hospital, a shop, on public transport, etc, forget how well spaced people are. If you are breathing other folks' air for more than a few minutes, an N95 or better is what you should be wearing.