With many countries reducing restrictions implemented to slow the coronavirus pandemic, effective testing for an active COVID-19 infection or determining whether someone has (hopefully long lasting) immunity to this latest SARS virus, will become critical.

Here are a few references that explain how COVID-19 tests work, how the new serological (antibody blood tests) work and how accurate they are currently.

COVID-19 tests: how they work and what’s in development

There are two main ways to test for infection with SARS-CoV2 (the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 disease). The first is a very sensitive test that looks for the RNA of the virus using a technique called RT-PCR. A second type of test measures the antibody responses to virus in blood serum.

theconversation.com/covid-1...

Checking blood for coronavirus antibodies – 3 questions answered about serological tests and immunity

These tests look for antibodies that your body’s immune system generated to fight the infection. So, the tests detect the response to the virus, not the virus itself. They cannot be used early in infection, before a patient’s body has mounted an antibody response.

theconversation.com/checkin...

Coronavirus: how accurate are coronavirus tests? (False positives and negatives, with a great explanation of the impact of these on a real life example).

The meaning of a test result for an person depends not only on the accuracy of the test, but also on the estimated risk of disease before testing.

theconversation.com/coronav...

Why can’t we use antibody tests for diagnosing COVID-19 yet?

...it’s hard to make one that works. It’s difficult to craft a test that is specific enough to detect just SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), and not other similar viruses. More importantly for diagnosis of active cases, it’s difficult to craft a test that is sensitive enough to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies early on during infection.

theconversation.com/why-can...

Serology Tests in COVID-19: Are They Good Enough?

— Top official at major diagnostics company has questions

Shamiram R. Feinglass, MD, MPH, is chief medical officer at diagnostics maker Beckman Coulter, responding to the FDA policy adjustment last week on serology-based COVID-19 antibody testing.

Right now, we don't know the level of disease in our communities. We don't have enough data yet to determine if antibodies will give people immunity. We need to understand how to get people back to work safely and reopen our economy. In order to do that we need to test them. Before a vaccine is available, we need to decide how to decrease the public health risk. We have an urgent need for high quality tests capable of providing actionable results. We need a large amount of high-quality tests that we can process quickly that produce reliable results. These tests need to be available broadly. The right serology testing will help us find the answers we need to get us back to work, identify convalescent plasma, and develop a vaccine. It will be an important part of what helps us collectively to pull out of this crisis. It's going to take a lot of hard work to get us there. But we must stick to high standards for the good of global health.

medpagetoday.com/infectious...

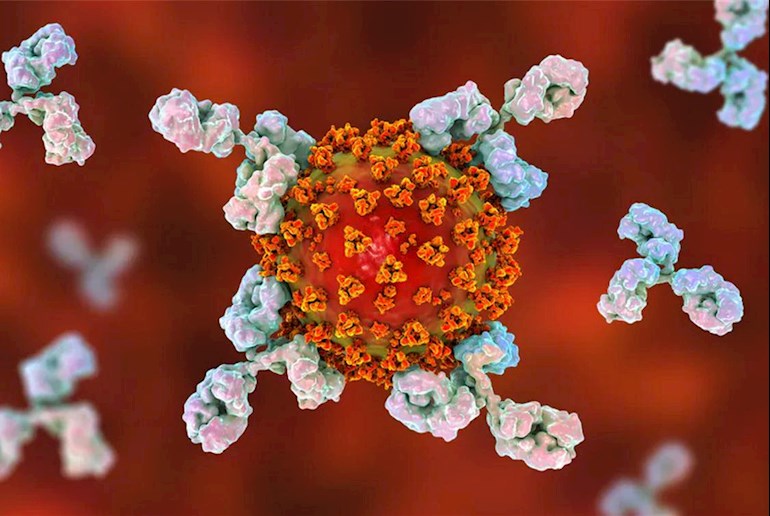

Photo: Shuttercock image showing the Y shaped antibody proteins locking onto the spikes of a SARS-CoV-2 virus and targeting it for destruction by our immune system

This is an unlocked post, which can be returned in Internet searches: healthunlocked.com/cllsuppo...

Neil