Results from double blind, peer-reviewed research show improvement among those who received extra oxygen, but not regular air

By NATHAN JEFFAY

13 December 2021

Breathing high rates of oxygen while sleeping can significantly reduce depression, a preliminary Israeli study has suggested.

Researchers from Ben Gurion University’s Faculty of Health Sciences recruited 55 depressed adults and got them to breathe from special tubes as they slept, every night for a month. Around half received regular air, which contains 21 percent oxygen, while the others received air with 35% oxygen content.

“Among patients in the control group, very few achieved even minimal improvement in symptoms of depression, but in the other group, 30% to 40% made notable improvements,” Dr. Abed N. Azab, the lead researcher in the peer-reviewed study, told The Times of Israel.

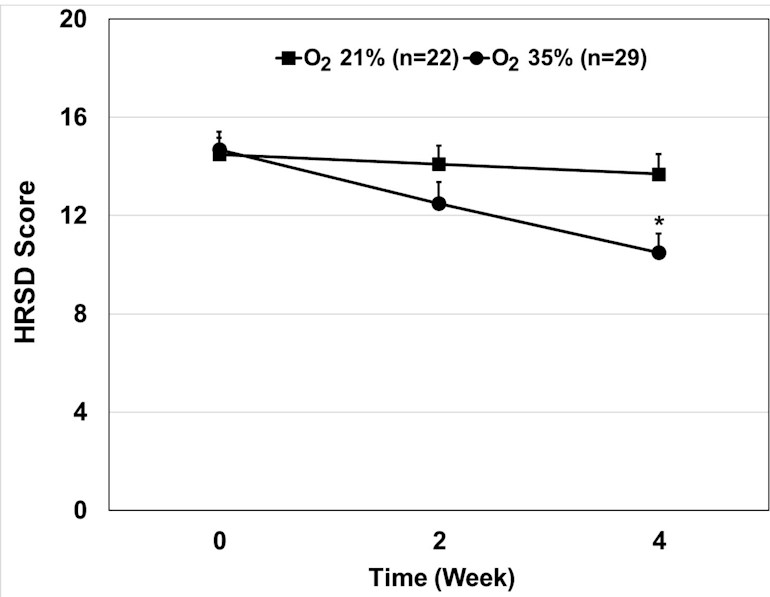

At the start of the month-long experiment, participants averaged 15 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, classified as moderate depression. Scores among the control group hardly changed during the experiment, but the average score among those who received oxygen steadily dropped, ending at around 10, which reflects a jump from moderate to mild depression.

Azab stressed that his research focused on regular oxygen, which is sourced easily and cheaply yet hasn’t been widely explored for depression, as opposed to special hyperbaric oxygen chambers, which are expensive and in scarce supply. “Oxygen is known to be very safe, and is also affordable,” he said.

He said that symptoms were assessed with standard criteria used by psychologists and psychiatrists, including the questionnaire-based Hamilton scale.

A graph showing that trial participants who received extra oxygen, represented by the line that falls, had lower scores in a depression assessment system, than the control group, as the experiment progressed. (Ben Gurion University)

Participants in the experiment, all of whom were diagnosed with depression, had canisters and special tubes installed in their bedrooms for use at night. The study was double blind to account for the placebo effect.

“We randomly divided the participants to those who received oxygen-enriched air and those who received normal air,” Azab explained. “Neither the participants nor the researcher on the ground knew who was getting what, and they received the treatment for seven to eight hours a night in their homes for a month.

“We saw a clear difference between those who received regular air and those who received the oxygen. Among those who received oxygen, we even had people ask at the end of the study to keep the machines at home because they helped — something we just didn’t see in the control group,” he said.

Azab said his team doesn’t know how the oxygen impacts symptoms of depression, but is hoping to answer that question through further research, and is also planning a larger-scale study to further explore the potential of oxygen.

“This was a small study but I hope we can replicate these results in a larger sample,” he added. “If this becomes a routine intervention, it could be an inexpensive way of treating depression and even — given that some depressed people commit suicide — save lives.”